MY LIFE AND TIMES AS A WRITER

One of the things that virtually all the subjects of my books have in common is a reluctance to talk about themselves. It is also one characteristic – possibly the only one – that I share with them. I believe it was Dr Johnson who remarked that ‘the best part of an author is to be found in his books’ – and Dr Johnson was, of course, a very discerning man! In any case my role as a writer (and for the most part biographer) has been essentially to act as intermediary between the reader and people infinitely more interesting than myself.

Over twenty years ago now, when I was first preening myself over the success of a book which, thanks entirely to royal subject matter, lavish pictorial illustrations, good timing and efficient marketing, became the ‘Times’ No 1 best seller for several months, a slightly older and very much wiser member of the writing profession told me the story of how Harold Pinter met a friend one day in the street. The friend turned to the small son she had with her and explained carefully to him: ‘This gentleman is a very good writer’. The little boy thought for a long moment and then, looking up at the great man, solemnly enquired of him, ‘Can you write a W?’

Somehow for me this has always kept the writer’s role in its proper perspective. If my own ‘life and times’ have been of any interest it is solely because of the people I have met along the way.

It was in fact Mother Teresa who launched me on my career as a more ‘serious’ writer. Following the success of the royal wedding book, I was asked by the publishing company for which I worked at the time, to produce ‘anything I could on Mother Teresa’. I wrote to Malcolm Muggeridge who was vigorously campaigning on her behalf in this country and he in turn referred me to Ann Blaikie, one of the first English women to assist Mother Teresa in her work in Calcutta and Co-founder with her of the International Association of Co-Workers. Ann immediately showed me in her home in Surrey a battered tin trunk containing the scraps of newspaper articles, letters and scribbled notes that were the ‘records’ of Mother Teresa’s international mission. She also informed me confidently that I had only to telephone Mother Teresa in Calcutta and the contents of these very unofficial archives would be mine to publish as I thought fit.

For three nights in succession I sat up into the early hours of the morning, trying to make contact with Mother Teresa. On the third she answered the telephone herself. By then Malcolm Muggeridge had written ‘Something Beautiful for God‘, the book which really made the world aware of her work, and there had been a few others. It was enough, Mother Teresa told me. There was no more material. But with all the irritability of one who had lost three night’s sleep and all the arrogance of youth, I presumed to argue. I had seen lots of material, I told her, in Ann Blaikie’s old tin trunk.

Unwilling perhaps to be unkind, she suggested we meet when next she came to London. We did so some months later and in the sparsely furnished ‘parlour’ of one of the Sisters’ London homes I experienced for the first time her gift for giving her whole attention to the person she encountered. She gave me her permission to write, adding with characteristic pragmatism that she hoped I was not putting any of my own money into the venture. Apparently, Nobel laureate though she already was, she had no inkling that her consent to that my first ‘real’ book with all its defects and limitations, would be enough to open up a multitude of doors. I did not know then but would afterwards discover that precisely those qualities which in this world’s terms might well have counted against me were what contributed to the favourable outcome of our encounter: my youth, my inexperience, my sense of inadequacy and uncertainty.

That London meeting with Mother Teresa was to prove the first of many. As with all those who came to her seeking to understand, she put me to work. Experience had shown her that to know the problem of poverty intellectually was not really to comprehend it. In order really to understand it, you had, in her words to ‘dive into it, live it and share it’. You had really to touch the reality of the poor.

Put to work in the Home for the Dying in Kolkata

I was to be put to work, serving food to the down and outs of London, washing the tiny babies who slept sometimes three to a cot in the children’s home in Delhi, cutting the hair of the women in the home for the dying in Calcutta and undertaking numerous other tasks in numerous other places. I was to discover how the tiny unresponsive body of a child deprived of human contact can spring suddenly to life at the warmth of an embrace, and how vitally important merely the silent touch of a warm hand is to a dying ‘untouchable’, to a leprosy sufferer who has known only brutal rejection or to an ostracised AIDS patient.

The experience of being directed just to hold a dying baby in your arms and love it until the tiny spark of life in it is finally extinguished, or of endeavouring to distract a woman whose body is half consumed by rats as someone tries as painlessly as possible to remove the maggots from her wounds, is never forgotten. People with skin hanging in loose folds from their bones, children with stomachs distended with worms, and hollow eyes turning blind for lack of vitamins, lepers with leonine features and open, infected wounds – these are images that burn themselves upon the soul and can only heighten regard for those who daily touch the reality of them and do not turn away.

Someone once remarked somewhat rashly to Mother Teresa that he would not touch a leper for a thousand pounds. ‘Neither would I’, was her instant response, ‘but I willingly do so for the love of God’. The motivation for her service was rooted in the words of St Matthew’s gospel: ‘Whatsoever you did to the least of these my brethren, you did it to me’. The vision which she held out to the world was of Christ present, Christ hungry, thirsty, imprisoned or lonely, in the distressing disguise of the poorest of the poor, and of Christ simultaneously present in the Eucharist and offered to sustain in order that the cry of the poor person for nourishment and, above all else, for love, might not go unheard.

When first I met Mother Teresa she was eager that attention should not be unduly focused on the poverty of India. She had by then begun to travel in the West. She had been taken on a tour of London by the Simon Community. She had seen the strip clubs of Soho and the people sleeping under the tarpaulins which draped the scaffolding of St Martin’s in the Fields. Among the methylated spirit drinkers and the drug pushers, a young man well fed and well-dressed, took an overdose of barbiturates before her very eyes – because, he said, his mother did not want him. The poverty of the West – the spiritual deprivation, the loneliness, the breakdown of family life – Mother Teresa maintained, was a problem so much more difficult to solve than the physical poverty of the so-called Third World. No matter how powerfully those images of the material poverty of India or Africa might have carved themselves upon my consciousness, my book was not to be centred unduly on them but rather to invite people to identify the poor person in their own country, on their own doorstep, in their own family.

For a while next I was to dip my toe into the world of the rich and powerful and discover for myself, if not for the first time, then perhaps with greater immediacy than before, its limitations. Among the many opportunities that came my way as a result of that first book on Mother Teresa’s international mission was an invitation to have an input to a feature film about her life. I helped to put together a script which was as faithful as possible to the facts. But when the first potential producers saw it, they wanted major changes. The simple explanation Mother Teresa provided for all her actions: namely ‘for Jesus’ did not suit contemporary requirements for psychological complexity. The film’s financiers could not understand, as others have since failed to understand, Mother Teresa’s lack of ‘hidden agendas’. Nor could they, I suspect, understand how Mother Teresa might perceive their own pursuit of wealth and power and their adherence to the principles of personal expediency as a form of poverty more acute than those skeletal images which spoke so heart-rendingly to audiences from the screen.

Not surprisingly, Mother Teresa was nervous of what film-makers might want to do with her life (although the French writer, Dominique Lapierre was subsequently to be responsible for an excellent film with Geraldine Chaplin presenting a remarkably accurate portrayal of Mother Teresa). While we were working together on the first script, Dominique had also begun writing City of Joy, the book which was to open the eyes of the world not merely to the dreadful living conditions of the occupants of one of Calcutta’s most poverty-stricken slums but also to the indomitable human spirit which prevails there, to the warmth and dignity of the slum-dwellers’ relationships, to their capacity for sharing the little they have – to the spiritual riches of the materially poor. Dominique had developed a deep affection for those poverty-stricken people of India, who still knew how to make a kite out of the bits and pieces that others had thrown away and laugh as they made it soar over the improvised rooftops of the slums. They were the bearers of a message of life and hope and joy for those of us who appeared to have so much. One day he casually handed me the opening page of City of Joy in French and asked me to put it into English. I did so and before I knew what had happened found myself engaged in translating the whole of the rest of the book.

And so one project led to another. India has a saying: ‘when the disciple is ready the guru appears’. I had no intention of becoming a disciple and the subjects of my books would certainly not cast themselves in the role of gurus but somehow each one seemed to bring with it a timely awakening of truths perhaps hitherto known but dormant. Dominique was unable to accept an invitation from the Taizé community to discuss the possibility of a book about its founder, Brother Roger, so I was sent instead.

With Dominique Lapierre and his wife and the Reverend James Stevens OBE, founder of the Udayan home for children affected by leprosy.

In 1940 at the age of 25, Roger Schutz, the son of a Swiss Protestant pastor had crossed the border into war-ravaged France to attempt to live out a vision of reconciliation in the tiny village of Taizé. At a time when Europe was torn asunder, Roger had asked himself why such conflict should exist between people in general, and why between Christians in particular. He had felt himself called to establish a community in which reconciliation and peace would be made concrete day by day, to live what he refers to as ‘a parable of communion’. By the time of my first visit over a hundred brothers from Catholic and Protestant traditions were living in community at Taizé. Handfuls of others lived in tiny ‘fraternities’ amongst the poor in different parts of the world, and thousands upon thousands of young people of all nationalities and creeds had been drawn to share in this visible sign of a quest for unity and peace.

Deeply intuitive, and, although approaching seventy, possessed of that childlike quality which the Gospel calls for, at our first meeting Brother Roger poured forth in Swiss French, sentences that were rarely completed and ideas that were left hanging suspended somewhere in the atmosphere. Intellectually my knowledge of French was not up to it but somehow we understood each other. ‘Poetry – that is what the Church should be,’ he announced suddenly as together we surveyed the undulating Burgundy countryside from the window of his room. My heart leapt to agree and, to cut a very long story short, two years later I was able to publish a book about his life and vision.

Brother Roger communicated to me – more by a kind of ‘osmosis’ than by words – his mystical vision of the Church not as I had previously been inclined to see it as the corpse of Christianity but as the vital body of a God made man because he so loved the world and in order that all might know the truth of the resurrected Christ. He spoke of the Church as the presence of the Resurrected Christ in the lives of humanity, a presence which created a communion which was both hidden and visible. He spoke of how in the heart of God, the Church was as large as all the world. He spoke of how his yearning for reconciliation was rooted in the desire to bring together the separated members of this suffering invisible and visible body.

With Brother Roger at Taizé

Listening to the people who flock to Taizé, living at times in more visible communion with the poor in different parts of the world, had made Brother Roger acutely aware of the suffering that is part of the universal human condition. Together with Mother Teresa, he had identified the existence not only of the visible homes for the dying in countries such as India but also of the invisible homes for the dying of Western society, of those deeply wounded by broken relationships, psychological neglect and spiritual doubt. So it was that he emphasised the necessity for the Church to be a place which has at its heart the people of the Beatitudes, the peace-makers, the meek, the poor in spirit, and to be above all a place of compassion in the true sense of the word, i.e. that of suffering with.

There came a point when Mother Teresa specifically asked me to write a book about her link for sick and suffering co-workers. Many years previously a Belgian woman by the name of Jacqueline de Decker had been undertaking Gandhi’s village work in India. In 1947 she walked half way across India to meet the as yet little known Mother Teresa, and wanted to join the embryo order of her Missionaries of Charity. But Jacqueline was suffering from serious health problems and on her return to Belgium for what she had thought would be a brief spell of treatment, she discovered that she had a severe disease of the spine further complicated by her body’s tendency to produce abnormal fibres. Eventually she was informed that in order to avoid total paralysis she would have to undergo a number of operations. Gradually it became apparent that she would never be able to return to India. The realisation was initially a bitter one. Jacqueline contemplated suicide but in the Autumn of 1952 she received a letter from Mother Teresa:

‘Today I am going to propose something to you. You have been longing to be a missionary. Why not become spiritually bound to our society which you love so dearly? While we work in the slums, you share in the prayers and the work with your suffering and your prayers. The work here is tremendous and needs workers, it is true, but I also need souls like yours to pray and suffer. ‘

What Mother Teresa envisaged was a kind of ‘spiritual power house for the Missionaries of Charity’.

On 12th April 1953 her first twenty-seven novices were to be professed. She wanted a sick and suffering link who would be prepared to offer joyfully a life of suffering and pain, and pray specifically for each one of these Missionaries of Charity. Jacqueline, recovering from one of more than thirty operations she has undergone to date, found people amongst her fellow patients who were prepared to assume this extraordinary role, and as, with time, the number of Missionaries of Charity grew to over two thousand so too did the number of sick and suffering co-workers.

Jacqueline de Decker – Mother Teresa’s “sick and suffering self”

By the time I met Jacqueline de Decker her torso was rigidly encased in a corset and her neck was restricted by a surgical collar. Yet from her home in Antwerp she managed not only to co-ordinate the Link for the sick and suffering, but also to look after the welfare of some 2,000 prostitutes. At that stage she could still drive a specially adapted car. She took me careering round the red light district of Antwerp in this vehicle to visit her ‘girls’. We drank rough alcohol with women who manifestly looked forward to her visits and laughed about the destiny that had brought together a daughter of one of Antwerp’s most influential families and the desperate individuals who struggled to maintain children and dependants, or simply their own survival, through prostitution. I, a former police officer, sat bemused in the illuminated windows of brothels while Jacqueline sorted out the domestic or health problems of her ‘girls’. ‘They need a comprehensive heart to help in their own language not just a soup kitchen’, she once informed Mother Teresa in no uncertain terms. Jacqueline had manifestly learned this language.

The link for the sick and suffering co-workers brought me into contact with people suffering from every conceivable illness from elephantiasis to chronic depression. And yet from most, if not all, of these encounters I came away in some unexpected way uplifted. I remember one French woman in particular. (I would think of her specially as some years later I found myself on a barrio in Honduras consuming the beans that are the staple food of the poor there.) As a student doing voluntary service overseas, this woman had worked briefly sorting such beans in a factory in Latin America. There she had picked up a parasite which some years later erupted in her system. The most sophisticated medical treatment could not rid her of it and she was in effect rotting from the inside out. The worst part about it was that no one wanted to share a hospital room with her because of the smell of her putrifying flesh. Her suffering, physical and psychological, seemed to me appalling. And yet she and many others had somehow taken on board Mother Teresa’s message that suffering shared with Christ’s passion could be a ‘wonderful gift’, that the prayers of the suffering had a special potency and that their lives were not therefore devoid of dignity, meaning or purpose.

Their letters to their linked Sisters and to Jacqueline, filled with human frailty as they were, contained nevertheless – or perhaps precisely for that reason – many lessons for me, not least that somehow and sometimes suffering could be the medicine that deepens our humanity. There was furthermore a single common prayer which emerged, if at times only from between the lines of their letters namely : ‘Assimilate and use the shortcomings and the shadows of my life!’ Stripped and weak to the point of being unable even to pray, many were possessed of that most easily lost of all virtues, humility, a genuine belief that they were useless dependants on God alone.

My travels were in time to take me from the black townships of South Africa to the nomadic people of the Sahara and everywhere I went there was poverty, suffering or oppression. There was joy and beauty in these experiences. There was also revulsion, admiration, awe, guilt, outrage, the craving radically to change the world and a profound sense of inadequacy and impotence because such a change was clearly never to be effected by me.

Mother Teresa maintained that we are not called to be successful but to be faithful. Her vocation was not to change political systems and social orders but to begin always with the individual. ‘Ek, ek, ek’ – ‘one by one by one’, was the principle of her revolution, a revolution which she claimed, ‘came from God and was made by love’. In her vision if a book brought one soul, just one single soul, a little closer to God then it was worth all the agony that went into it. We are not, she insisted, required to do great things but only small things with great love. Our value as human beings, in whom Christ is uniquely present, is not in our doing but in our being. Such a vision, though counter-cultural like so much of what Mother Teresa had to say, was readily grasped at, offering as it did a certain peace of mind, but it was not fully digested overnight.

But in 1989 I had the opportunity to spend some time in the l’Arche homes for people with learning difficulties founded by Jean Vanier. In l’Arche people with mental handicaps and assistants live together not as educators or carers and cared-for but as what Jean describes as sharers in a life of communion, that relationship of real sharing and opening to one another, based on humility and trust, which we all crave in order to break down the barriers of loneliness.

I went first to the original community in Trosly-Breuil, France with a far from uncommon sense of being mysteriously drawn and yet afraid. I was drawn to Jean Vanier’s insistence, born of more than twenty-five years of living in communion with mentally handicapped people, that God had chosen the weak, the ‘crazy’ and the despised of our world to confound the strong, the clever and the respected. I was drawn to his identification of the poor, the weak and the vulnerable as prophets for our world. But I had little previous experience of mentally handicapped people and was acutely aware of my own overdeveloped if unwarranted sensibilities when it came to such superficial considerations as table manners and hygiene. I think also I may have sensed in advance the disturbing way in which what Jean Vanier had to say about the tensions between the rich, powerful and effective and those who are powerless and have no voice in human affairs, would touch upon my own experience.

The rich, Jean Vanier tells us, regard the poor and the weak as problems and seek to resolve those problems according to their own vision and theories. They will not listen to the oppressed and the distressed. Sometimes they even want to prevent their very existence. In each one of us there is a strong resistance to change and that is why the rich cannot enter into dialogue with the poor; for such a dialogue inevitably calls upon the rich person to change. The cry of the person in need inconveniences those who are comfortable and satisfied with themselves and their lot. The anguish of handicapped people, salivating, sometimes violent, uninhibited and crying out for real affection, reveals our anguish, their shadows our shadows and so we turn away.

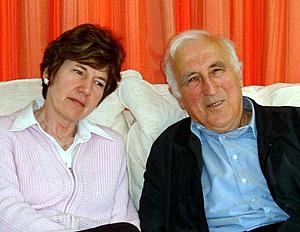

Kathryn Spink with Jean Vanier at her home in Surrey

What is more, there is a rich person and a poor person in each one of us. Jean Vanier, having left the navy in 1950 at the age of 21, as he puts it ‘to follow Jesus’ and having in 1964 invited two people with learning difficulties to come and live with him, was to discover very early on in the development of l’Arche, his own poverty. It became apparent to him that to love someone did not mean primarily doing things for that person but revealing to him/her his value, helping him to rediscover his self confidence. This was by no means easy for one who knew about efficacy, competence, organisation, action, teaching and even about generosity, but who had yet to learn how to take time to understand others and allow them to reveal the needs, the beauty and the meaning of their lives. He was to discover not only the tension between the ‘poor’ man and the ‘rich’ man outside but the same tensions within himself.

Part of the message of l’Arche was that in order really to enter into relationships of communion it is essential that we recognise our own poverty. ‘Communion’ for Jean Vanier is a state of being present one to another with a deep respect of difference. It is also a state of grace, the fruit of shared love, a place which is very close to the things of God. It is frequently deepened in silence and is linked much more to the body.

Communion for Jean is frequently associated with gentle moments lived with the profoundly handicapped, for whom as he puts it, ‘there is a lot of body and not much word’. If I may just read you what he has says about bath time with Eric, for example, who is almost completely blind and deaf:

It was an occasion when a deep communion could be established: when we would touch his body with gentleness, respect and love. In hot water Eric relaxes; he likes it. Water refreshes and cleanses. He has a feeling of being enveloped in a gentle warmth. Through water and the touch of the body there was a deep communion that was created between Eric and myself. It was good to be together. And because Eric was relaxed, it made me feel more relaxed. He has complete trust in the person who gives him a bath. He is completely abandoned. He no longer defends himself. He feels secure because he senses he is respected and loved. The way he welcomed me, the way he trusted me, called forth trust in me. Yes, Eric called me forth to greater gentleness and respect for his body and his being. He called forth in me all that is best. His weakness, his littleness, his yearning to be loved touched my heart and awakened in me unsuspected forces of love and tenderness. I gave him life; he also gave me life. These moments of communion are the revelation that God has created deep bonds between us.

Not all relationships with people with mental handicaps are as obviously characterised by gentleness as those with Eric. Some people with learning difficulties are enclosed in a world of depression and revolt and are full of aggression. Jean has cited the example of Pierre with whom he shared a home for a year and whose screams of anguish and violence awakened in him the realisation that he was actually capable of physically assaulting someone very much weaker than himself. Both communion with Eric and Pierre’s awakening of our murky depths confront us, Jean Vanier tells us, with the truth of our being. We are all of us tired of competition and aggression but we also have in us shadows, violence and turmoil which we fear but which we must discover and accept, if we are to live in accordance with the truth of our being and use our energies to love.

Jean dispatched me round the world to see how l’Arche was lived in different cultures. There have been many times when in slums or deserts or places of danger I have had, to say the least, grave reservations about what writing the kind of books that I do entails. One night in Honduras, researching the book on l’Arche, I shared a mud hut with two assistants and three handicapped people, one of whom slept in a hammock suspended above me. We were close to the Nicaraguan border. During the long, dusty bus journey to the barrio that day armed men had boarded the vehicle and I had been held at gunpoint for a while. The sound of gunfire was still audible in the distance. It was suffocatingly hot and during the night I discovered in a very uncomfortable way that the person in the hammock above me was incontinent. Next day, stripped of the last vestiges of any facade of smartness or competence by my very limited knowledge of Spanish and of the Honduran way of carrying out the simplest of daily tasks, I knew what it was in a very small way to be ‘handicapped’. It is at times such as this that I have actually experienced the reality of Mother Teresa’s assertion that ‘self-knowledge puts us on our knees’ or of Jean Vanier’s claim that ‘the discovery of our wounded humanity brings with it the need for prayer, the desire for God to bring about the healing of hearts.’ And it is at times such as this that it has invariably been those labelled ‘poor’ and ‘weak’ who have come to my rescue.

Christ in the broken but life-giving bodies of the poor – for Jean Vanier, as for Mother Teresa, there is a mysterious potency in suffering and vulnerabilty. And in the warmth and encouragement which belied yet stemmed from the profound suffering of those rejected for the strangeness of their bodies or for having something missing from their minds, that mystery became an actuality.

Travelling round the l’Arche communities, I learned to trust that it would be the ‘handicapped’ people who would most astutely sense my weariness, feelings of inadequacy, my poverty and in an intuitive subtle way, effect some healing. I found myself overwhelmed with gratitude for precisely those people I had feared, for Johnny whose twisted, toothless smile was so infectious, for Lita whose uncontrollable dribbling I no longer noticed, for Dave who with his pipe between his lips would solemnly entertain me with stories of his early life that were so flagrantly but absorbingly untrue, for Peggy who concealed her disappointment so graciously when I and not, as she had expected, Princess Diana arrived for dinner. She had been shown the cover of my Royal Wedding book as an indication of who the prospective guest was and had sweetly confused the picture of the subject with the author.

Research for my next book about Little Sister Magdeleine, foundress of the Little Sisters of Jesus, entailed three weeks journeying across the Algerian Sahara, sharing the life of the Tuareg nomads, walking in the footsteps of Little Sister Magdeleine and of the man who first inspired her, Charles de Foucauld, who saw the vast arid expanses of desert as a way of disposing of everything within one that was not of God. Such journeys are physically rigorous but there is a great attraction for me in a life devoid of barriers with only a goat and camel hair tent to separate me from the great contemplative silence of desert and sky, amongst people for whom inch’allah, ‘God willing’, is not only a leitmotiv of conversation but actually the guiding principle of their lives.

The problem for me has always been that of somehow holding on to the silence and recollectedness of the desert and returning from the world of the have nots to the haves without judging humanity – either my own or other people’s. But in Little Sister Magdeleine there was the example of one whose goal was, above all else, unity between people of all nations, creeds and classes, for she could bear no division between people of any kind. The one thing she would not tolerate was proud, judgmental eyes or words which might divide or wound. Little Sister Magdeleine believed so strongly in the importance of God having assumed our humanity in the form of a tiny infant in all his vulnerability and surrender, that she made the spirituality of the manger the cornerstone of her new congregation and urged her Little Sisters to be ‘human before religious’. At the same time, for Little Sister Magdeleine the beauty and importance of the manger derived from the fact that it contained the whole Christ, God and humanity together. Here again was the mystery of weakness: the tiny infant reaching out to the world from the manger was also the omnipotent God. I was to discover just how far- reaching the message of Little Sister Magdeleine’s essentially hidden life had been in Moscow in 1998 when the Russian edition of my biography was launched. It was January and bitterly cold. It was the first time there had been a launching of that kind for a religious book. The hall was packed, simply because of the affection of the Russian people for a woman who, since 1956, had travelled behind the Iron Curtain in a specially adapted camper van with a concealed compartment for the Reserved Sacrament, just to be a prayerful presence amongst suffering people.

Since Mother Teresa’s death and the publication of my ‘authorized biography’, I have often been asked what our relationship has done for me and I find myself answering in many different ways according to the questioner and the moment. One thing is sure, however: directly or indirectly she introduced me to an extraordinary range and richness of experience. At the same time the journey on which she launched me has been a journey downhill, an awakening to the vision of the fool, to smallness, to the truth that the poor person is not just the leper or even the lonely alchoholic but somehow or other also within me, yet the trust that precisely in that poverty and smallness lies a certain potency.

The journey has brought with it the vision of humanity bound together by shared suffering, compassion, companionship and joy in the mystical body of a Christ who came to set all people free, not only those who live explicitly by his example but all people, of all races and classes and all nations of the world.

It has brought with it also the confirmation that there is meaning and purpose in human life, even in my life. The landmarks are all so clearly there, in the people encountered, in things heard, in the books that come to hand, in the manner in which circumstances unfold. Brother Roger’s veiled reality has been rendered visible through a multitude of individuals and events.